Parliament Faction Links Lacking Accountability to Deaths of Political Prisoners in State Custody

|

| Mostafa Mohebbi was fired from his position as the head of the State Prisons Organization in Tehran Province in June 2019 after a political prisoner’s death in state custody prompted condemnation by rights groups. |

JULY 8, 2019

Defense Attorney: Firing Prison Officials Won’t Keep

Political Prisoners Safe

One month after

political prisoner Alireza Shirmohammadali was murdered in

the Greater Tehran Central Penitentiary (GTCP)

after being unlawfully held in a ward with inmates convicted of violent crimes,

two prison officials have been fired while the unofficial policy that

precipitated the tragedy remains in place.

The results of a

judicial investigation into his death have not been made public. But a

parliamentary faction has created a proposal to help counter what it identified

as the “serious problem” of prisoners dying in state custody.

A Tehran-based

defense attorney who has represented political prisoners told the Center for

Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) that firing officials without ensuring that prisoners

are held in safe conditions means more preventable deaths could occur.

“The question is,

why has nothing been done to separate the political prisoners now that this has

become an issue?” said the lawyer who requested anonymity for security reasons.

“Well, the

judiciary’s spokesman Mr. Esmaili has said we don’t have any political

prisoners in Iran and therefore it’s not an issue,” added the attorney. “Of

course, that’s only his personal opinion; the law clearly defines political

prisoners.”

According to

Article 2 of Iran’s Political Crimes Law, individuals can be

imprisoned for various peaceful acts including “insulting or slandering the

heads of three branches of state, the chairman of the Expediency Council, vice

presidents, ministers, members of Parliament, members of the Assembly of

Experts and members of the Guardian Council” as well as “publishing

falsehoods.”

Political

prisoners in Iran are also arrested and prosecuted under “national security”

related charges for peaceful actions including removing their

headscarves in public or defending political prisoners as lawyers.

During a press

conference on July 1, Gholamhossein Esmaili said,

“We don’t have political prisoners. These people committed crimes against

national security.”

He also stated

that the law requiring the separation of prisoners on the basis of their

convictions had been carried out “to an acceptable degree, especially in

Tehran.”

According to

Iranian law, prisons are required to divide prisoners according to the nature

of their convictions.

Article 69 of the

State Prisons Organization’s regulations states: “All convicts, upon being

admitted to walled prisons or rehabilitation centers, will be separated based

on the type and duration of their sentence, prior record, character, morals and

behavior, in accordance with decisions made by the Prisoners Classification

Council.”

But political

prisoners continue to be transferred to and held in

prisons and wards with inmates convicted of violent crimes or with substance

abuse issues.

For example,

the GTCP was built in 2015 primarily for holding suspects and inmates

convicted of drug-related offenses.

But the judiciary

has also used it to unlawfully incarcerate peaceful activists and dissidents

including Shirmohammadali.

Treating the Symptoms, Not the

Problem

|

| Deaths in State Custody of Political Prisoners |

After Iranian

activists and human rights organizations condemned the circumstances of

Shirmohammadali’s death, two officials were dismissed. But the Iranian

government has not implemented measures to ensure that other political

prisoners would not also be put in harm’s way.

On June 20, 2019,

the head of the State Prisons Organization (SPO) in Tehran Province, Mostafa

Mohebbi, was dismissed and replaced by Heshmatollah Hayatolgheyb, who formerly

headed the SPO’s office in Fars Province.

The SPO, which

has offices in every province, is responsible for prisoners in Iran and

operates under the judiciary, which means it cannot be investigated by

Parliament.

The director of

the GTCP (also known as Fashafouyeh Prison), Hedayat Farzadi, was fired on July

1.

On July 2, the

state-funded Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) reported that

Mohebbi’s removal was the result of an investigation carried out by a committee

set up by the judiciary to look into Shirmohammadali’s death.

The results of

that investigation have not been made public.

Arrested on July

15, 2018, Shirmohammadali was allegedly stabbed to death by a convicted drug

trafficker with the help of a fellow convict, a source with detailed knowledge

of the circumstances of Shirmohammadali’s death told CHRI in June 2019.

Shirmohammadali

had been sentenced in February 2019 to eight years in prison for the charges of

“insulting the sacred,” “insulting the supreme leader” and “propaganda against

the state” and was awaiting the result of his appeal before his death.

Three months

prior to being stabbed, he had gone on hunger strike in protest against the

prison’s unsafe conditions.

It is not clear

whether Mohebbi and Farzadi, who were fired after Shirmohammadali’s death, have

been banned from government service or transferred to other state positions.

Little is known

about the new SPO chief in Tehran. But during Hayatolgheyb’s tenure as the SPO

head in Fars Province, political prisoner Mehdi Hajati was incarcerated in Adelabad

Prison in a ward with prisoners convicted of dangerous crimes.

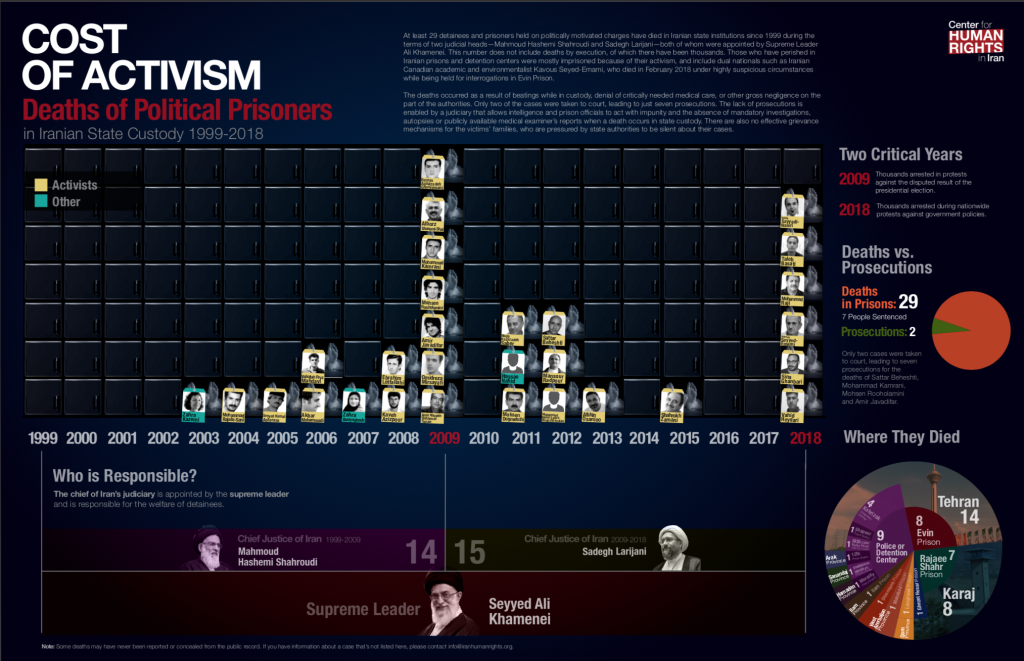

Between 2003-18,

at least 29 political prisoners died in Iranian state custody, according to

investigations by CHRI. That number does not include deaths by execution.

The deaths

occurred as a result of beatings while in custody, denial of critically needed

medical care, or other gross negligence on the part of the authorities. Only

two of the cases were taken to court, leading to just seven prosecutions.

The lack of

prosecutions is enabled by a judiciary that allows intelligence and prison

officials to act with impunity and the absence of mandatory investigations,

autopsies or publicly available medical examiner’s reports when a death occurs

in state custody.

Parliamentary Faction Proposes

Way to Counter Lacking Accountability in Iranian Prisons

After

Shirmohammadali’s death, Abdolkarim Hosseinzadeh, the head of the Citizens

Rights Faction in Iran’s Parliament, wrote to

newly appointed Judiciary Chief Ebrahim Raisi on June 16 stating that the

incident “was a sign of a very serious problem” in the country’s prisons and

detention centers.

“In order to cure

a disease we first have to admit its existence and then tackle it without any

bias,” Hosseinzadeh said in his letter.

“After the

reported deaths of several individuals in prison in 2018, we, as the people’s

representatives, insisted on visiting Evin Prison and other facilities and

detention centers… and as a result of the visits, as well as meetings with some

of the prisoners’ families, we concluded that the missing link is the lack of a

supervisory organization independent of the prison system.”

The letter

continued: “The Citizens Rights Faction’s solution to the problem was a

proposal to move the SPO from the judiciary to the Justice Ministry … under the

close supervision of judicial and legislative branches.

Currently, the

SPO only answers to the judiciary and cannot be investigated by Parliament.

It is not clear

how far the parliamentary proposal has gone in the legislative process.

At least six political prisoners died in Iranian

state custody in 2018 under suspicious circumstances. The State Prisons

Organization and the judiciary to which it reports are responsible for keeping

prisoners safe but to date no organization or individual has been held

responsible for the deaths.

In an interview with

the reformist Kaleme website on June 26, Shirmohammadali’s mother, Mahnaz

Sorabi, said she had been left with several unanswered questions about her

son’s death.

“Tell Mr. Raisi

that I’m seeking justice for my son’s blood. I want to know what hands were

involved behind the scenes,” Sorabi said.

No comments:

Post a Comment